April 10, 2023

The growing role of investment funds in euro area real estate markets: risks and policy considerations

Introduction

REIFs play an important role in euro area CRE markets. REIFs are investment funds that invest primarily in real estate. They invest either directly in physical property or indirectly via the purchase of shares or debt issued by companies that themselves invest in real estate. REIFs therefore provide a valuable channel of financing and investment in euro area CRE markets, reducing reliance on bank financing and thus diversifying the investor base. However, in the past decade the REIF sector has grown significantly and now accounts for 40% of CRE markets in the euro area. This means that developments in the real estate market and REIFs have become increasingly interdependent. Instability in the REIF sector could therefore have systemic implications for CRE markets, which could in turn affect the stability of the wider financial system (because of financial institutions’ direct exposure to CRE) and the real economy (for example, because of the effects on collateral values and lending) (see Horan, Jarmulska and Ryan, 2022). Recent empirical analysis for the euro area suggests that REIF activity has implications for prices in residential real estate markets (Bandoni et al., 2023), even though the share of REITs in the total residential real estate market is much smaller than their share in the overall CRE market.

This is particularly relevant given the deteriorating outlook in real estate markets. There are clear signs of vulnerability in real estate markets, including declining market liquidity and price corrections, driven largely by uncertainty in the macro-financial outlook and by monetary tightening.

The potential for CRE market uncertainty to affect REIFs has been highlighted by recent stress events outside the euro area. In the United States, Blackstone Real Estate Income Trust (BREIT) recently experienced an increase in redemption requests, primarily from Asian investors. As a result, BREIT had to limit redemptions in line with its own withdrawal limits, undertake substantial property sales and source new investment to ease liquidity pressures. Similarly, in the United Kingdom many REIFs have imposed redemption gates following an increase in redemption requests triggered initially by the gilt turmoil and more recently by macro-financial uncertainty and the negative CRE market outlook.

Previous shocks have also shown that euro area REIFs are exposed to significant liquidity risks, so any deterioration in CRE markets could be magnified in the REIF sector. Grill et al. (2022) find that open-ended real estate funds were more likely than other fund categories to suspend redemptions after the onset of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. This is largely because it is difficult to accurately value and sell illiquid property assets during stress periods, which may increase the likelihood of investor runs. Similarly, any deterioration in current CRE market conditions may also increase the potential for large redemption requests. If appropriate liquidity management tools (LMTs) are not in place, REIFs could have to resort to asset fire sales, thus amplifying market stress. Consequently, we focus in this article on the liquidity vulnerabilities of open-ended REIFs.

Open-ended REIFs are vulnerable to redemptions because of the structural liquidity mismatch between their assets and liabilities, which, along with their importance for euro area CRE markets, underscores the need for a common and comprehensive policy framework for REIFs. These funds are subject to a structural liquidity mismatch when they offer frequent redemptions to their investors while holding illiquid real estate assets. Policies to reduce the vulnerability from the liquidity mismatch should include more active use of LMTs, as well as direct measures focusing on both the assets and liabilities sides of REIFs. Section 2 of this article examines the importance of REIFs in euro area CRE markets. Section 3 looks at CRE market stress, while Section 4 examines how this stress could be amplified by REIFs’ vulnerabilities. Section 5 addresses the consequent need to enhance the resilience of REIFs.

2 The role of real estate funds in euro area real estate markets

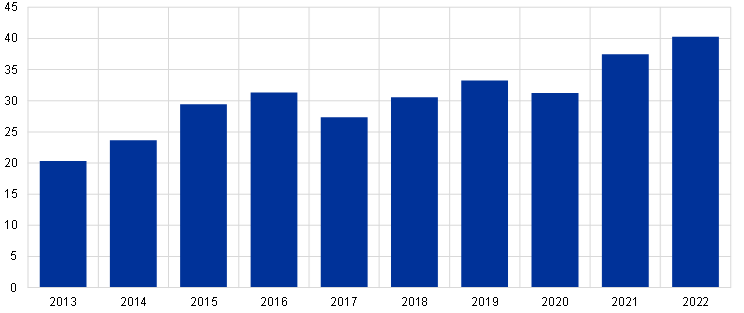

Euro area REIFs have grown significantly in the past decade. The net asset value (NAV) of REIFs more than trebled between the fourth quarter of 2012 and the fourth quarter of 2022, increasing from €323 billion to €1,040 billion (Chart 1, panel a). Open-ended REIFs account for 80%, or €835 billion, of the NAV of all REIFs. These funds are primarily located in five countries (Germany, Luxembourg, France, the Netherlands and Italy), which account for most of the growth in the sector. However, there has also been extensive growth in other countries. This reflects the role of REIFs as the largest investor in the euro area CRE market. Between 2013 and 2022, the value of REIFs’ real estate assets as a proportion of the total value of the euro area CRE market increased from 20% to 40% (Chart 1, panel b), highlighting the growing importance of REIFs for this market.[4]

Chart 1

Growth of REIFs and their share of the euro area and national CRE markets

a) Net asset Value

(EUR billions)

b) Real estate assets as a share of the euro area CRE market

(percentages)

c) Real estate assets as a share of national CRE markets

(percentages)

Sources: ECB IVF statistics, Real Capital Analytics (RCA), Cushman & Wakefield (C&W), Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI) and ECB calculations.

Notes: Real estate assets include non-financial assets (i.e. direct holdings of physical real estate), debt securities and shares and other equity.

Looking at the share of REIFs in national CRE markets, it can be seen that the market footprint and type of exposure vary across countries, with particularly large market shares in certain countries. In several euro area countries, notably Luxembourg, Ireland, the Netherlands and Portugal, the real estate assets of REIFs represent over 30% of the value of the national CRE market. However, this figure includes exposures to real estate held through financial instruments (namely debt securities and equities) that are more likely to relate to cross-border investments.[5] For example, in Luxembourg the majority of CRE holdings, especially those in the form of financial instruments (Chart 1, panel c), relate to investments in other European countries (ALFI, 2022). Similarly, in the Netherlands and Ireland, CRE investments in the form of financial instruments also tend to be cross-border investments. At the same time, these cross-border investments increase the interconnectedness of euro area CRE markets, with the risk that stress in one jurisdiction might spill over to CRE markets in other jurisdictions. By contrast, non-financial assets relate to direct holdings of physical real estate, which may be more domestically focused. For example, in Ireland these direct holdings relate to domestic real estate and represent 40% of the national CRE market (Chart 1, panel c) (also see Daly, Moloney & Myers, 2021). REIFs’ holdings of non-financial assets are also large relative to the national CRE market in other countries (notably Portugal, Italy, Germany, France, Greece and the Netherlands). Consequently, REIFs’ activities are likely to have a material impact on CRE markets in these jurisdictions.

3 Vulnerabilities in commercial real estate markets

The importance of REIFs and their potential to amplify CRE market dynamics is particularly concerning in light of growing vulnerabilities in the CRE market itself. Euro area CRE markets have been subject to a series of major shocks over recent years. With the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the office and retail segments were immediately and severely affected by lockdown policies. These parts of the CRE market remain subject to uncertainty over the effect of the resulting changes in behaviour, such as the shift towards hybrid working and e-commerce. While the market had shown signs of recovery in 2021 and early 2022, rapidly rising financing costs and wider macro-financial uncertainty now pose fresh challenges. In addition, strong price growth in the years leading up to the pandemic may have resulted in overvaluation in CRE markets, creating space for a large price correction in the event of adverse shocks (ECB, 2019). The severity of these shocks is clearly visible in survey data. These show unprecedented spikes in the percentage of investors reporting deteriorating financing conditions and a market downturn, along with a steady increase in the percentage of investors describing prices as expensive or very expensive (Chart 2, panel a).

Chart 2

The outlook for euro area CRE markets has deteriorated sharply and implications for market activity and pricing are already visible

a) Investors surveyed reporting deteriorating market conditions and overvaluation

(percentages)

b) Number of transactions in euro area CRE markets – annual growth (%)

(percentage change)

c) Prime CRE market valuations – annual growth (%)

(annual percentage change)

Sources: Panel a): Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) and ECB calculations; panel b): RCA and ECB calculations; panel c): Jones Lang LaSalle (JLL) and ECB calculations.

Notes: The euro area aggregates in panels a) and c) are calculated based on GDP-weighted averages. The country sample in panel c) is made up of Belgium, Germany, Ireland, Greece, Spain, France, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Austria, Portugal and Finland. Last observation for all charts in 2022 Q4.

In the final quarters of 2022, risks associated with tighter financing conditions and macro-financial uncertainty began to materialise, with a sharp drop in transaction numbers and falling prices. Market activity – and by extension market liquidity – dropped sharply at the end of 2022, with 44% fewer transactions in the final quarter of that year than in the same quarter of 2021 (Chart 2, panel b). Market intelligence attributes this to the wait-and-see approach adopted by investors in the face of uncertainty about future developments in financing conditions, inflation and the macro-financial environment. In addition, the literature indicates that transaction numbers can drop before a large market correction as buyers revise down their bid prices faster than sellers revise their asking prices (van Dijk et al, 2020). Price growth in prime euro area markets also dropped sharply in the second and third quarters of 2022, with annual price growth in prime office markets reaching -14% (Chart 2, panel c). At present, the only price data available are for prime markets. However, market intelligence indicates that conditions may be substantially worse in non-prime markets as demand for more environmentally friendly buildings is driving a structural shift in investor and occupier demand towards newer, energy-efficient buildings (ECB, 2021).

Vulnerabilities in the CRE sector are widespread across the euro area, but the outlook for countries with a pronounced REIF presence does not appear favourable. Shocks arising from the pandemic were particularly focused on the office and retail sectors. While investor demand in the industrial segment recovered quickly, demand for office and retail sectors has never returned to pre-pandemic highs. In fact, recent challenges arising from higher funding costs and macro-financial uncertainty are affecting demand for all types of CRE, and investor demand across all segments dropped sharply at the end of 2022 (Chart 3, panel a). Meanwhile, the outlook for national CRE markets appears to be mixed, with particularly adverse developments seen in markets where there is also a substantial fund presence (see Section 2). In countries such as Austria, Germany, France and the Netherlands, a high share of investors are signalling both a downturn and signs of overvaluation (Chart 3, panel b). These countries have also seen particularly large substantial valuation corrections (Chart 3, panel c).

Chart 3

While current vulnerabilities affect all sectors within the CRE market, some countries appear to be harder hit than others

a) CRE investor demand dynamics

(percentage changes)

b) Investors surveyed reporting market in downturn and overvaluation

(percentages)

c) Annual percentage valuation changes, Q4 2022

(annual percentage change)

Sources: Panels a) and b): RICS and ECB calculations; panel c): JLL and ECB calculations.

Notes: Panel a): The investor enquiry indicator is defined by RICS as “the perception of the change in the number of investment enquiries per property during the last three months”. Last observation in 2022 Q4. Panel c): the euro area aggregate is based on a GDP-weighted average.

4 Structural vulnerabilities in the REIF sector

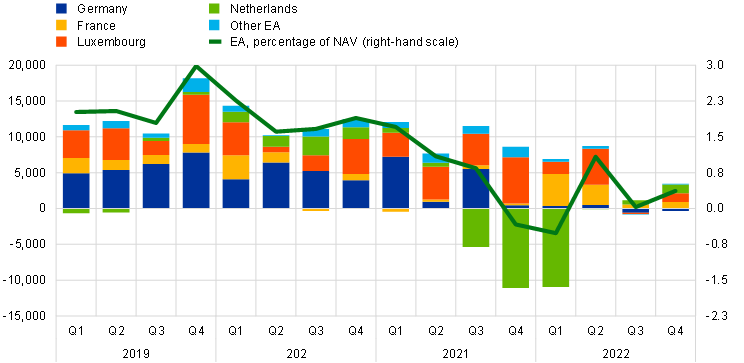

A key vulnerability in REIFs is the mismatch between the liquidity of fund assets and redemption terms. When redemption terms are shorter than the liquidation period of the fund’s portfolio assets, large and sudden investor redemptions can lead to tensions. According to ESRB (2023), REIFs with a mismatch between asset liquidity and redemption terms accounted for as much as 31% of the total open-ended REIFs market as at the third quarter of 2021. In addition, Chart 4 (panel a) shows that in some countries where REIFs account for a substantial part of the CRE market (for instance France, the Netherlands and Ireland), the majority of such funds have an open-ended structure, while cash buffers are relatively low.[6] In contrast, the vulnerability is expected to be of a magnitude lower in countries where cash levels are higher or where more funds are closed-end (for instance Italy and Portugal). As conditions in CRE markets have become more challenging, flows into REIFs have started to slow and have even turned negative in some jurisdictions (Chart 4, panel b).

Chart 4

While there are large variations across the euro area, some countries have a large share of open-ended funds but relatively low cash buffers

a) Share of CRE market and cash holdings

(percentages)

b) Quarterly net inflows

(EUR millions)

Source: ECB IVF statistics.

Notes: Panel a): NAV of open-ended versus closed-end funds as a percentage of the domestic CRE market, and cash holdings as a percentage of NAV; panel b): quarterly net inflows in EUR millions (left-hand scale) and euro area aggregate net inflows as a percentage of NAV (right-hand scale).

Procyclical behaviour resulting from the liquidity mismatch could adversely affect the stability of CRE markets. Forced liquidation of real estate assets to meet investor redemptions might lead to downward pressure on CRE prices given the large footprint of REIFs. In addition, the liquidity mismatch may give rise to a first-mover advantage if costs associated with investor redemptions are borne by the remaining investors in the fund. In the absence of appropriate LMTs, which are currently not harmonised across Europe and remain limited in some jurisdictions (ESMA, 2020), this first-mover advantage might further amplify outflows in times of stress and thus increase the risk of a negative externality in the form of fire sales (Fecht and Wedow, 2014). This could create a negative feedback loop in which price declines resulting from fire sales drive further redemptions and vice versa.

Investors may anticipate price corrections because funds’ portfolio assets are revalued infrequently. The NAVs of REIFs may only reflect price developments in underlying CRE markets with a lag because portfolio assets are revalued infrequently. If investors expect that the NAV of their REIF will decrease, this will provide them with an incentive to redeem their shares. Especially during periods of low transaction activity in CRE markets, frequent valuation of portfolio assets is challenging (Weistroffer and Sebastian, 2015). Difficulties in accurately valuing illiquid property assets during stress periods could increase the likelihood of investor runs.

Cross-border investments by euro area REIFs give rise to interconnectedness in euro area CRE markets. Common ownership of real estate assets resulting from diversified REIF portfolios connects CRE markets within the euro area. CRE price corrections in one country might therefore spill over to CRE markets in other countries. More generally, any adverse macroeconomic development in one country that triggers outflows from REIFs might spill over to CRE markets in other countries. On the upside, cross-border diversification reduces the impact of country-specific shocks, thereby increasing REIFs’ resilience.

Leverage may further amplify vulnerabilities in the REIF sector and lead to spillover effects in other parts of the financial system. First, leverage implies greater sensitivity towards fluctuations in real estate prices. During market downturns, leverage therefore magnifies the losses faced by investors, which might exacerbate outflows and amplify vulnerabilities stemming from the liquidity transformation performed by REIFs. Second, the use of leverage creates links between REIFs and other financial institutions that act as credit providers. As a result, tensions in the REIF sector might spill over to other financial institutions, affecting the stability of the wider financial system.

5 Policy options for addressing REIFs’ vulnerabilities

Policies should be developed to address the structural vulnerabilities of REIFs given the risks they pose to CRE markets and wider financial stability. The structural vulnerabilities of REIFs and the risk of CRE market corrections being amplified represent a strong argument for establishing a policy framework to address these macroprudential issues. Policies should be developed to enhance the ability of REIFs to manage spikes in liquidity demands and to internalise the costs of redemptions which can arise during a market stress. Alongside the consistent application of leverage limits, policies that directly reduce the underlying liquidity mismatch, such as lower redemption frequencies and longer investor notifications, could be implemented to strengthen the resilience of the REIF sector. In addition, although REIFs are regulated under the Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive (AIFMD)[7], they may be subject to a range of national requirements which can go beyond the minimum standards for alternative investment funds. This means that the regulatory framework for REIFs may vary across jurisdictions. Since many REIFs have both cross-border exposures and a cross-border investor base, there is a need to ensure that the regulations governing REIFs are consistent across the euro area.

REIFs should have a range of LMTs available to the fund manager which can be implemented to manage the liquidity position of the fund in all market conditions. In order to address the liquidity mismatch of REIFs in the near term, should risks materialise, a range of LMTs should be available to the fund manager to implement in times of stress. It is important that these LMTs are both effective and usable. All REIFs regulated under the AIFMD are required to have the ability to suspend redemptions when the fund is experiencing high levels of redemption requests. However, suspending redemptions is a blunt instrument that funds are often reluctant to use given the associated stigma and costs (see Grill et al., 2022). Therefore, funds should also implement more targeted LMTs such as redemption fees and redemption gates. Making a broader liquidity management toolkit available to managers would enhance their ability to effectively manage the fund’s liquidity and thereby strengthen its resilience. The use of these tools should be guided by supervisors to ensure that it is consistent across funds, while there is a role for the European Securities and Markets Authorities (ESMA) in ensuring that the approach taken by supervisors is also consistent across countries.

LMTs alone cannot address the underlying structural vulnerability of REIFs, so policies that fundamentally reduce liquidity mismatch should also be explored. By their nature, REIFs hold inherently illiquid assets, and this should be reflected in the redemption structure of these funds. Certain countries do not allow open-ended real estate funds given the illiquidity of their portfolios. A closed-end structure might be more appropriate, as it would ensure a higher level of resilience and in turn provide benefits to both the manager and the investor in times of stress. If an open-ended fund structure is preferred, policy measures that address the structural liquidity mismatch should be implemented. On the assets side, a policy of increasing the share of liquid assets held could be explored, as it would reduce the liquidity mismatch. Policy measures worth exploring that focus on the liabilities side include lower redemption frequencies, longer notice and settlement periods, and longer minimum holding periods.[8] More frequent valuations, while not directly addressing the liquidity issue, would improve the transparency of a fund and the value of its assets, thereby reducing the risk of first-mover advantage. These measures would reduce the liquidity mismatch that makes REIFs vulnerable to spikes in redemption requests. In turn, the measures would enhance fund resilience and reduce the risk of CRE market corrections being amplified. Given the cross-border nature of these funds, it would be important to ensure that these measures were applied in the same way by all supervisors in the EU.

Open-ended funds are currently the focus of international policymakers as they seek to address the liquidity mismatch and boost fund resilience. The recent Financial Stability Board (FSB) report on the assessment of the 2017 recommendations on addressing liquidity mismatch in open-ended funds found that there had been no improvement since the publication of the recommendations (FSB, 2022). The FSB has designed a liquidity bucketing approach for open-ended funds which would link the liquidity requirements of the funds with the liquidity of the underlying assets. This bulletin seeks to contribute to the FSB’s work by identifying measures that could be applied to open-ended funds falling with the “illiquid” bucket.

Source: European Central Bank

Legal Notice: The information in this article is intended for information purposes only. It is not intended for professional information purposes specific to a person or an institution. Every institution has different requirements because of its own circumstances even though they bear a resemblance to each other. Consequently, it is your interest to consult on an expert before taking a decision based on information stated in this article and putting into practice. Neither Karen Audit nor related person or institutions are not responsible for any damages or losses that might occur in consequence of the use of the information in this article by private or formal, real or legal person and institutions.