September 20, 2023

As policymakers stress the need for further insights into developing economic trends, awaiting to learn the lagged impact of prior interest rate hikes, the coming week’s timely flash PMI survey data should provide useful guidance on economic growth and inflation.

In this article we review the latest PMI signals and seek to assess what a key indicator, the PMI’s backlogs of work index, tells us about the likely further path of the world’s major economies.

Data dependence amid uncertainty

Upcoming flash PMI data for the major developed economies will be especially closely watched by markets, given the widely cited ‘data dependence’ of the US Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), European Central Bank (ECB) and Bank of England (BOE). All three central banks have made it clear that they are unsure of the near-term paths for growth and inflation, and hence the necessity of further rate hikes, and have underscored how their upcoming decisions will be swayed by the data flow.

To recap on the latest policy stance, the FOMC is widely expected to hold rates at its September meeting waiting for more news on the economy prior to likely hiking again in November. The Bank of England is meanwhile forecast to hike for a fifteenth successive time at its September meeting on Thursday, though may then sit on its hands to await more news, especially on stubbornly higher wage growth. The ECB has already hiked in September, for a tenth time, but hinted this may be its last. Alas, some of the ECB’s more hawkish policymakers have already stressed that a December hike may be needed.

While it would be odd to think that a policymaker wouldn’t always be data dependent to some extent, there’s clearly an unusual amount of uncertainty around at the moment.

The upcoming PMI data should therefore help guide near-term policy, especially as the surveys are often referred to by policymakers, both in their assessments of global economic conditions and narrower national or regional trends.

Stagflation?

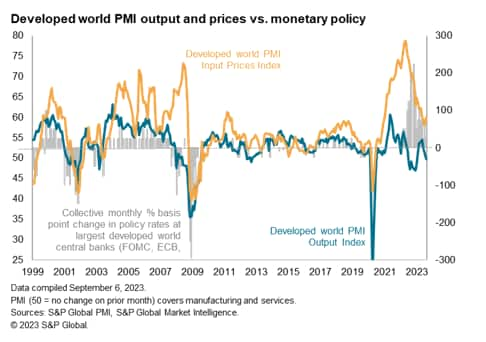

Worryingly, the latest signals have been hinting at the worst possible scenario for policymakers: stagflation. This unwelcome combination of stubborn inflation and no growth means that any further tightening of monetary policy adds to already-elevated recession risks.

To bring ourselves back up to speed on the latest PMIs, the surveys showed global economic growth slowing for a third successive month in August. The headline global PMI slipped to its lowest since the current global economic upturn began in February and signals annualized worldwide GDP growth of only around 1%. That compares dismally with a pre-pandemic average of 3%.

The PMI for the developed world was especially disappointing, falling into contraction territory for the first time in seven months in August, led by a third month of falling output in the Eurozone and a renewed decline in the UK. The US also came close to stalling, leaving Japan as the only major developed economy sustaining a robust expansion.

This regional divergence can of course be at least in part explained by the fact that Japan has not seen the policy tightening, nor cost-of-living crises, that Europe and the US have witnessed recently. Note that in the US and Europe, a key development in recent months has been the faltering of this year’s recent revival of service sector growth. Previously-fast-growing consumer services and financial services sectors, which had enjoyed a post-pandemic growth spurt, are now seeing falling demand, often attributed to higher interest rates.

Manufacturing meanwhile remains in the doldrums, with output falling globally for a third month running in August. Although only modest, the current rate of production decline looks set to accelerate as demand – as measured by new orders inflows – is falling at a faster rate than production.

These weak demand conditions filtered through to a near-stalling of jobs growth in the developed world. This represents a major contrast to the strong job gains seen throughout much of the two and a half years prior to the summer.

The global PMI selling price index meanwhile fell from 53.7 in July to 53.4 in August, its joint-lowest since December 2020. The overall rate of inflation nevertheless remained elevated by pre-pandemic standards due to some bottoming-out of manufacturing prices, higher oil prices and stubborn wage-led service sector price gains.

As to what comes next, there are some PMI sub-indices which can give some clues as to future performance. One, in particular, the Backlogs of Work Index, is showing some interesting signals.

Backlogs of work hint at near-term risks to the downside

The PMI’s Backlogs of Work Index measures the amount of orders that companies have received but have yet to work through. This pipeline, or stock, of work is a key gauge of how busy companies are likely to be in the coming months, absent any major changes in new order inflows. It is also a good guide to capacity utilization. If backlogs are rising, companies will generally expand their activity levels in the months ahead to meet these unfulfilled orders, increasing output and also often raising employment. Conversely, falling backlogs mean that companies may become worried that they are running out of work, and will hence moderate their output and even cut workforce numbers.

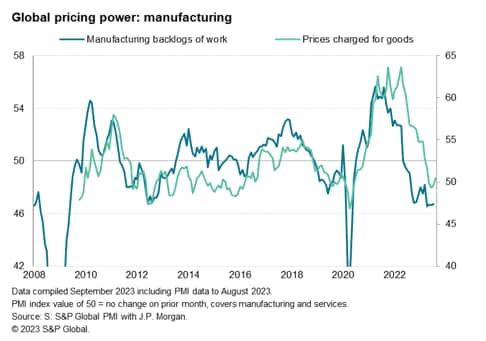

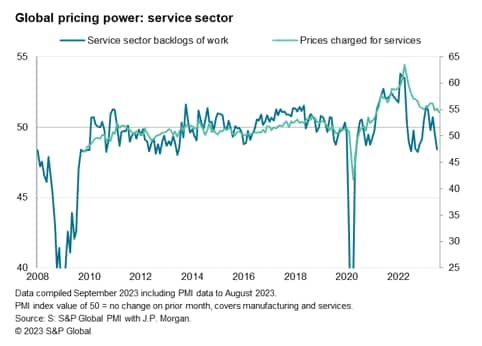

One other valuable application of the Backlogs of Work Index is therefore in also signaling pricing power: if backlogs are rising, it means firms are likely to be able to change more for their goods and services (as demand is exceeding supply), and vice versa when backlogs are falling.

So what are backlogs of work telling us at the moment?

Unfortunately, backlogs of work fell across the developed markets at a rate not seen for 14 years in August if the early lockdown months of 2020 are excluded.

In manufacturing, backlogs of work in fact fell worldwide for a fourteenth consecutive month in August, reversing the unprecedented buildup of unfulfilled seen during the height of the pandemic. Improved supply chains have facilitated the manufacture of a broad variety of items after the constraints and shortages seen during COVID-19 lockdowns. However, with new order inflows for goods having likewise now fallen for 14 straight months, these backlogs are being rapidly depleted.

In the service sector, the pandemic trend has been different. Backlogs have tended to accumulate after the lockdown or containment measures were relaxed. One such period has been in early 2023, following the removal of restrictions by China. The resulting global surge in demand for services such as travel and tourism often meant companies could not meet the influx of orders resulting in backlogs. These backlogs peaked globally this year in March, and are now falling again, dropping in August at the fastest rate since last November. Exclude the pandemic months, and global service sector backlogs of work have not been falling this fast since 2012.

In both manufacturing and services, the recent declines in backlogs of work have been especially marked in the developed world.

Outlook

Looking ahead, therefore, the steep reduction in developed world companies’ backlogs of work hints at further downside risks to output, and also to employment. These pressures will add to recession risks. However, at the same time, the fall in backlogs of work signals reduced pricing power, meaning inflation may prove less sticky than many are currently fearing.

Hence, stagflation may be avoided, but the suggestion from the PMI data is merely that inflation pressures are cooling at the cost of a possible recession.

Source: S&P – Chris Williamson

Legal Notice: The information in this article is intended for information purposes only. It is not intended for professional information purposes specific to a person or an institution. Every institution has different requirements because of its own circumstances even though they bear a resemblance to each other. Consequently, it is your interest to consult on an expert before taking a decision based on information stated in this article and putting into practice. Neither Karen Audit nor related person or institutions are not responsible for any damages or losses that might occur in consequence of the use of the information in this article by private or formal, real or legal person and institutions.